As an institution, the Burgtheater transcends its role as a mere stage. It’s part of the Viennese consciousness; a place to be seen and to see, a one-time plaything of political intrigue, and a symbol of Vienna’s rise, fall, and rise again from the ashes of war.

Exciting, no?

- The institution dates back to the 1740s

- The current building opened in 1888

- Damaged by fire in 1945, reopened in 1955

- See also:

From court to national theatre

(Late 19th-century photo of the old Hofburgtheater (right) on Michaelerplatz. The building was replaced by an extension to the Hofburg palce complex). Photo courtesy of the Rijksmuseum)

The Burgtheater traces its roots back to 1741, when an enterprising entrepreneur sought permission to convert a disused building on the Michaelerplatz (close to the imperial court) into a stage.

Despite the initial blessing of Empress Maria Theresa, the new theatre struggled to establish itself.

Fortunes changed in 1776, however, when Emperor Josef II turned the building into the official court and national theater: the first of its kind in German-speaking Europe.

Josef invested much of his own time in the institution, both behind the scenes and as a regular member of the audience; his presence – quite literally – drove the theatre’s success.

A ticket to a play now came with the chance to see the Emperor himself. This proved quite an attraction to both the gawping masses and to the rest of the aristocracy, who fell over themselves to be seen at a production graced by the presence of his imperial majesty.

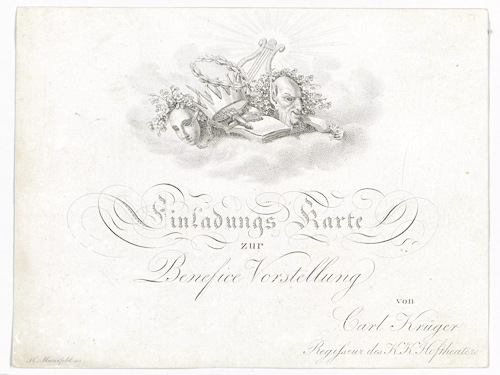

(Invitation to a benefit performance from Carl Krüger, director of the Hoftheater, dated sometime before 1828, engraved by Heinrich Mansfeld; Wien Museum Inv.-Nr. 231875/52; excerpt reproduced with permission under the terms of the CC0 licence)

Not that court influence proved ideal for artistic freedom. Censorship was rife at the time, and few performances escaped a rewrite.

Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, for example, lacked a certain key element for an alleged tragedy when the Viennese performance ended with the couple living happily ever after.

The “new” Burgtheater

In 1874, work began on new premises for the theater: one that could better meet the demands of modern theatrical productions.

Urban planners picked a choice spot opposite the town hall on Vienna’s Ring: the boulevard that encircles the city center.

The relocated imperial Hofburgtheater opened in 1888, with a refurbishment 11 years later to correct poor seating arrangements.

(The Burgtheater around 1888 at the time of its opening; August Stauda (photographer); Wien Museum Inv.-Nr. 226688; excerpt reproduced with permission under the terms of the CC0 licence)

The old site made way for a new façade for the adjoining Hofburg complex, though you can see, for example, its rooftop stone eagle in the Theatermuseum.

In 1918, the imperial theater became the Burgtheater (the first time the current name was used officially) and passed into the ownership of a state more concerned with rebuilding a country post-WWI than financing plays.

The institution persevered though, despite the economic deprivations of the time, until another war and Hitler brought further trouble.

With tragic inevitability, the arrival of the Nazis in the 1930s saw Jewish members of the theater company “removed”, the exclusion of works from “inappropriate” playwrights, and performances begin with a Nazi salute from an attending officer or party member.

In 1945, the theatre’s troubles came to a head. Already damaged from American bombs, the Burgtheater caught fire as the Soviet army “liberated” the city.

(Entrance ticket for the reopening of the Burgtheater on October 15th, 1955; the ticket price included use of the cloakroom; Wien Museum Inv.-Nr. 227297; reproduced with permission under the terms of the CC0 licence)

Performances continued elsewhere, but the building only reopened in all its finery in 1955: the same year Austria regained its independence from the allied powers.

The opening play that day was König Ottokars Glück und Ende by the renowned 19th-century Austrian writer Franz Grillparzer (whose former office you can see in the Literature Museum and whose memorial fills one end of the rose garden in the neighbouring Volksgarten park).

Today’s Burgtheater remains one of the world’s most important theaters: a cultural bastion in a city replete with historical significance. The Emperors and dictators are long departed, but the show goes on.