So what’s it like going to a place of such distinction and history as the Vienna State Opera House (Staatsoper)?

It’s not a bad joint to be fair. The singers seem quite reasonable, and the house band can play a decent tune.

And they sell booze.

Ok, perhaps there’s a little more to it than that. Read on for my experience.

- Book a classical concert experience* for your Vienna trip

- See also:

La Bohème

(The opera house at night)

If you open your big book of outstanding cultural encounters, then a performance at the Staatsoper sits right up at the top of the list…sandwiched somewhere in among seeing The Birth of Venus at the Uffizi gallery or Macbeth in Stratford.

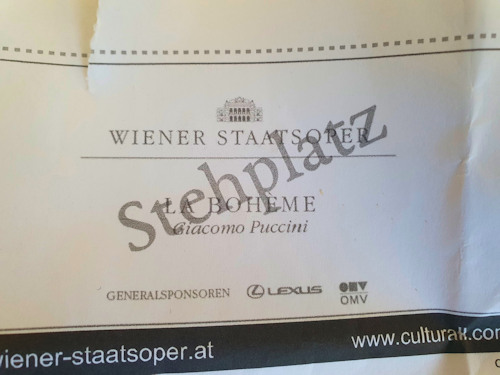

La Bohème cost me an astonishing €4 (not a typo) for a pre-booked parterre standing ticket, which means just above stage height in the rear centre of the auditorium. So one of the best views you can have, and I’ll never ever get over how this is possible at that price. Bravo, Vienna!

But I digress.

I began the evening by making myself look halfway decent. Not easy when you’re a middle-aged writer who works from home. My one decent shirt with a collar turned out to be in the wash.

(My standing space ticket)

Normally, I’d read up on the opera before attending but time was at a premium around the Advent performance date, so my wife provided a quick summary: “someone has tuberculosis and dies.”

I can’t imagine a greater challenge for an opera singer than filling the Staatsoper with your voice while also pretending to have TB. Perhaps it was Puccini’s little joke. Or perhaps it’s simply that opera is opera, not theatre.

To enter the Staatsoper is to allow yourself to be transported to another place and era. A time of refinement and opulence. The magnificent staircases dominate the vestibule, the crowds a mix of classical opera goers and tourists taking selfies.

I was due to meet my opera-loving friend at our viewing position, rather than outside as usual. Which meant finding my way around on my own for the first time.

Fortunately, numerous members of staff stood ready to politely point me in the right direction, and my genetic ability to play the forlorn and lost Englishman also brings out the best in people.

“Follow the green carpet,” said the young lady, making me feel like some kind of environmental Dorothy on the way to Oz.

Oz, in this case, was a small section for standing tickets. Arriving too late to claim a place among the cushioned stanchions that offer respite for weary feet, I was obliged to stand on the centre stairs.

(Since my visit, the Staatsoper has changed the standing system so tickets come with a fixed numbered stanchion position.)

(A photo of the composer of La Bohème from 1920, published by Brüder Kohn KG (B. K. W. I.) and photographed by Ludwig Gutmann; Wien Museum Inv.-Nr. 57309/107; excerpt reproduced with permission under the terms of the CC0 licence)

We standing ticket owners form a diverse folk: multiple languages and ages, and clothing that ranges from full blown opera style to jeans and a t-shirt.

Out in the seats, the audience seems older, better dressed, and more comfortable (but considerably lighter of pocket).

But what of the actual opera?

Not having a stanchion meant no screen with subtitles, either. So this was a visual and audio experience bereft of text and story. And what a marvellous experience it still was.

The stage transformed itself across the piece. The first and final acts played out in a dilapidated Parisian apartment, where moments of stillness and silence felt like viewing a masterful Flemish painting.

(Enter 1830s Paris via modern-day Vienna)

Act 2 took in a street market and café, Act 3 a snowy city scene. All as good and real as anything that might come out of a film studio (Franco Zeffirelli was responsible for the production and set design).

After several visits to the Staatsoper, it becomes easy to take the elegance of the experience for granted. In the interval, for example, we enjoyed a glass of white wine in the Mahlersaal, near a piano that once belonged to Gustav Mahler himself. History surrounds you.

Back in the auditorium, with no text to read and no understanding of the Italian, I relied entirely on the emotion communicated by the voices and music produced on stage and in the orchestra pit.

Closed eyes allowed singers and musicians to reach in and wrap themselves around my heart. To transport me into a cold artists’ abode in France, where all that truly matters is the joy and pain of love. Where human frailty and emotion transcend the decades. Just voices and music.

And that, I guess, is what a night at the (Vienna) opera is really about. Not opulence and bow ties. Not wine and history. Just voices, music, and emotion.