A new exhibition invites you to swap the Danube for the Hangzhou Bay and follow the trail of Jewish refugees who fled Nazi Austria for Shanghai, creating their own “little Vienna” in the middle of China’s biggest city.

- Shines a light on Shanghai’s role as a “haven” for Jewish refugees

- Follows the lives and fates of the many Jews who fled Vienna for China in the late 1930s

- Runs Oct 21, 2020 – Jun 27, 2021

- All info also in English (including subtitles for the videos)

- See also:

- Current exhibitions in Vienna

The Viennese Jews in China

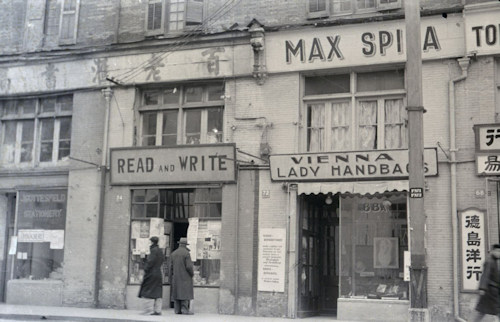

(The Vienna Handbags store, 1939 © Peggy Stern Cole, Photo: Melville Jacoby)

A recurring theme in some of the exhibitions at the Jewish Museum is the story of those Jews who managed to flee persecution in Austria at the end of the 1930s.

The tales are sometimes tragic, sometimes uplifting, and sometimes simple retellings of the common experience of many refugees everywhere: people striving to establish a new life in a strange place.

Finding a new host country proved a particular challenge when attempting to escape the Nazis. Which is where Shanghai comes in.

Enjoying a unique and convoluted international status (and already possessing its own Jewish community), Shanghai was one of the very few places that remained open to Jewish refugees and also required no entry visa.

The city thus provided a haven for Jews fleeing totalitarian European states in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s.

The absence of visa or other difficult entry requirements solved only part of the travel documentation issue for those wishing to leave Austria after the Nazis came to power. For example, the authorities still required exit papers of some kind.

Dr Ho Feng Shan (the Chinese Consul General in Vienna) added his name to the roll call of unsung heroes of European history by handing out thousands of “visas” that allowed their bearers to escape Nazi persecution.

Feng Shan’s actions, which went against the express orders of his superiors, received deserved recognition in 2000, when Israel’s Yad Vashem awarded him the title Righteous Among the Nations (he is one of only two individuals from China to receive this honorific).

A plaque honouring Feng Shan’s efforts also hangs in Vienna’s Beethovenplatz square, which is just under 15 minutes’ walk from the Jewish Museum.

The Little Vienna in Shanghai exhibition – wonderfully curated by Danielle Spera and Daniela Pscheiden – traces the footsteps of these refugees and shines a light on a relatively unknown part of the Jewish Viennese story.

We follow families on their formidable trip by sea or overland, witness their arrival and the challenges of a new environment, learn of their efforts to build a new life, and discover their fates during and after the Japanese occupation of Shanghai that saw Jews ostracised once again in a kind of ghetto.

Following the city’s liberation, most of the Austrian Jews moved on to other countries as it became clear that Shanghai would fall to Mao’s communists. Some even returned to Vienna.

A particular highlight of the story is the reversal of the Little China trope, with “Viennese” coffee houses, restaurants, and stores springing up in Shanghai, and the Jewish community keeping their Viennese and Jewish cultural traditions alive with appropriate events, entertainments, publications and associations. This earned the area around Hongkou the nickname, “Little Vienna.”

(It seems the word Vienna also had a certain cachet to it locally that worked as a kind of positive branding.)

The exhibition forms a glorious collage of photos, documents, objects, models, and videos that brings the Shanghai experience of the late 1930s and 1940s to life. The personal stories of various families run through it all like a thread, adding depth and emotion to the numerous personal items on display.

Like any exhibition of this nature, the contrasts are stark.

We learn of the high-society nightlife of Shanghai and the desperate circumstances of the would-be emigrants from Vienna.

We witness the unbridled joy of people travelling to a new life after the end of WWII, but also imagine the visceral fear that must have accompanied all the travellers as they crossed Europe in 1938 and afar in pursuit of safety.

We see, once again, the triumph of human endeavour and community spirit in the creation of a new existence abroad, but also contemplate a photo by the acclaimed US photojournalist, Arthur Rothstein, showing the same community scouring a list of concentration camp survivors.

The hardships of refugee life and the context that forced such a status upon the people involved always serve to make me weep. But so many stories of personal triumph and generosity (such as the help given to the Viennese Jews by the existing Jewish community in Shanghai) act as a reminder of the perseverance of the human spirit.

Not to mention the little stories and items that add an endearing humanity to the tale. For example, the bust of Beethoven that one music-loving family took to Shanghai with them (and all the way back again to Vienna after the war). Or the city’s Café Roy, where they could tell your homeland based on how you pronounced Kaffee (Germans got two sugar cubes in their coffee, the Viennese got three).

Dates, tickets & tips

The exhibition runs from October 21st, 2020 to June 27th, 2021. Just get yourself a normal entrance ticket to the Jewish Museum to see it (or use a relevant sightseeing pass).

Should you wish to enjoy some of the traditional Viennese coffee culture that helped inspire Little Vienna, then pop up the road to Café Hawelka, for example.

How to get to the exhibition

Little Vienna in Shanghai fills the large exhibition rooms on the first floor of the Jewish Museum’s main location on Dorotheergasse. See the museum page for travel tips.

Address: Dorotheergasse 11, 1010 Vienna