Ever wonder what you’d find behind the closed doors of a natural history museum? I popped into the Bird Collection of the Naturhistorisches Museum to explore life away from the public displays.

- Visit prompted by an important scientific donation by the Harrison Institute

- Modern science in historical rooms creates a unique ambience

- Museum collections prove a critical resource for today’s environmental challenges

- Ah, the leather-bound books!

- See also:

Birds, bones, eggs & more

(Birds from the Harrison Collection; press photo © NHM Wien, Alice Schumacher)

Most people know the Naturhistorisches Museum in Vienna as a public museum full of minerals, dinosaur skeletons, and more. A home to such items as the Venus of Willendorf, the bouquet of gems, and numerous creatures who ended their days beneath the delicate hands of the taxidermist.

However, around 60 scientists also work behind-the-scenes on projects in fields ranging from biodiversity and taxonomy to paleontology and impact craters.

This research sits at the forefront of science. As such, the future meets the past given the museum building itself dates back to the late 19th century.

That theme has even more resonance when you consider that much of today’s science draws on yesterday’s archive material…with many historical items acquired by curious emperors or collected by naturalists bearing maps labelled “here be dragons”.

The juxtaposition of modern research and historical surrounds within a centuries-long chronology of scientific endeavour holds a certain fascination. But what is the museum really like away from crowds of eager visitors?

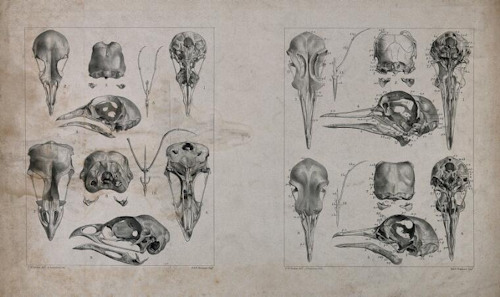

(Skull bones of birds: ten figures. Lithograph by J. Erxleben, after C.W. Parker, 1840/1860? Credit: Wellcome Collection; Public Domain Mark)

I had the opportunity to find out thanks to a donation…not one of money, but of birds; in 2022, the UK’s Harrison Institute donated its extensive collection of some 19,000 bird skins across almost 900 species to the Naturhistorisches Museum.

The accompanying press conference offered an insight into scientific research and collaboration at the museum, but also the work environment for the scientists. Let us begin with the latter.

The special nature of the institution becomes clear even before you enter the building from the side.

You pass a great stone statue where other museums might have a paper bin. And huge wrought iron lanterns hang down above the entranceway, only sliding glass doors hinting at the 21st century facilities within.

The familiar scent of science and natural history in the Bird Collection (part of the First Zoological Department) took me back to my days as a young biology student at Oxford. Not so much “here be dragons,” as “here be science”.

(Rooms of the bird collection at the NHM Vienna; photo © NHM Wien, Alice Schumacher)

But what does this all look like?

Do we have vaulted chambers with ancient cabinets of oak and glass? Polished brass instruments scattered across dark wooden tables? Some other cliché mirrored in a Victorian TV detective series?

Or is it all stainless steel and innovative instrumentation?

The answer is a little of both, just as you might imagine.

Tall arched ceilings and giant wooden doors topped by golden Roman numerals. Roof niches bearing 19th-century frescoes. Wood and glass cabinets. Books bound in ancient leather with such titles as Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux or Voyage of the Beagle: a bibliophilic paradise.

Ah, but also rows of metal storage facilities and walkways, fridges and photocopiers, multiple screens and hi-tech microscopes.

(Rooms of the bird collection at the NHM Vienna; photo © NHM Wien, Alice Schumacher)

Not to mention all the accoutrements that spell out avian science. A faded flyer from a scientific conference, posters from research presentations, mounted birds, and cabinet labels that whisper promises of feathered jewels within.

Labels like Psittacidae 2 followed by a flurry of species names. Or Franz Ferdinand – archival materials: presumably from that Habsburg archduke’s 1893 trip around the world that doubled as a scientific expedition.

What an extraordinary place to work, ever conscious of your role in a scientific lineage that dates back to before the time of Darwin and Newton.

But what of today’s science, as practiced by Dr. Swen Renner (Head of the Bird Collection) and his expert team?

The extensive and prestigious Harrison Institute collection, mostly built through the efforts of father and son James and Jeffrey Harrison, includes twelve so-called holotypes: physical specimens used as the representative associated with a particular description and species.

(James Harrison; photo © Harrison Institute)

These valuable holotypes now join around 1,000 others in the Naturhistorisches Museum’s bird collection, while the 19,000 skins provide a further critical resource to go with the existing 95,000 skins, 10,000 mounted specimens, 10,000 clutches of eggs, 1,000 nests, and thousands of other items such as feathers and skeletons.

It’s hard to fully comprehend the importance (historical and scientific), scope and physical presence of just this one collection among many held at the museum.

Consider, for example, that research into changes through time underpins our understanding of such issues as biodiversity, climate change, conservation, and population ecology.

As such, specimen collections play a crucial role in that context: the museum’s taxonomic studies and similar are the foundations on which much applied science then builds.

The donation came about thanks to the Harrison Institute’s changing focus toward, for example, education and training of young researchers across the world; sending the collection to the museum allows the resource to continue to play an active role in science rather than serve as a dormant archive.

The choice of the Naturhistorisches Museum as recipient reflects both the ongoing research commitment at the museum, but also a long collaboration between the two institutes. This cooperation continues in the training of foreign scientists.

So while we might admire the infotainment and displays in the public galleries, we should offer a nod of appreciation to those behind the scenes: those using the collections to help understand and meet some of the great challenges of our modern times.

Those bewhiskered naturalists of the past would no doubt approve.