The English name for Karlskirche (St. Charles Church) offers a bit of a clue to the building’s origins. Let’s talk about Saint Charles Borromeo of Milan.

- Built in the reign of Emperor Charles VI in honour of the patron saint of plague sufferers

- Reliefs include various plague references

- Architect Fischer von Erlach also designed other great Viennese landmarks

- See also:

What’s in a name?

(Eduard Peithner von Lichtenfels (Artist), Die Flusslandschaft an der Schwarzenberg-Brücke (gegen Karlskirche), around 1890, Wien Museum Inv.-Nr. 51001, excerpt reproduced under the terms of the CC BY 4.0 license; photo by Birgit und Peter Kainz)

We begin our story back in the 16th century and the city of Milan, which belonged to the Spanish Habsburgs at the time.

Saint Charles Borromeo (1538-1584) became Archbishop of the city at the tender age of 27, and many acts of sacrifice, humility, and compassion characterise his ecclesiastical career.

In particular, Charles proved a source of great comfort to the people of the city during the plague that struck in the 1570s.

Such paintings as St. Charles Cares for the Plague Victims of Milan by the famous Dutch baroque artist, Jacob (Jacques) Jordaens, depict his charitable and pastoral efforts during that time.

As such, Saint Charles is often referred to as the patron saint of plague sufferers.

(Saint Charles Borromeo in prayer; 1615 print based on a drawing by Giuseppe Agellio; image courtesy of the Rijksmuseum)

Now fast forward to early 18th-century Vienna, where a final plague epidemic raged across the city in 1713.

To his credit, the Emperor at the time (Charles VI) stayed in town. Given the circumstances, he also determined to build a church to honour St. Charles.

(I’m sure the fact the saint and the emperor shared the same name added to the appeal of the undertaking.)

Located on the banks of the River Wien, this new church offered views across to the main palace and displaced a vineyard on the same site. So you might say it turned wine into (holy) water.

The esteemed architect, Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, designed the building, though he died before its completion in 1737.

(The portal reliefs)

Despite its monumental majesty, Karlskirche did not even count as von Erlach’s greatest achievement. He created the astonishing State Hall of the National Library, for example. And also a little country cottage known as Schönbrunn Palace (albeit the final building owed much to modifications by Nikolaus Pacassi).

Von Erlach even had a hand in the plague column found on the Graben pedestrianised zone in the centre.

The epidemic-inspired origins of Karlskirche are reflected in more than just the church’s name, though.

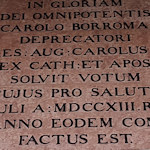

For example, the reliefs above the entrance portal show plague scenes, while those on the two giant exterior columns trace the life of Saint Charles. The man himself features significantly in the painted ceiling of the central dome.

P.S. A church by the river?

(View of the former Schwarzenberg Bridge and the Karlskirche behind, likely sometime between 1875 and 1885. Image courtesy of the Rijksmuseum.)

Should you visit Karlskirche, something significant does appear to be missing, though: what happened to the river?

The answer lies in one of the biggest urban upheavals in Viennese history.

As you can tell from the photo above (and the picture at the top of this article), the River Wien really did run very close to the church.

Fed up with constant problems with flooding, the authorities moved a huge stretch of the waterway underground.

In fact, I’m pretty sure the large water basin in front of today’s Karlskirche is positioned over the underground river, which emerges again in the nearby Stadtpark.

(You can actually visit the underground river on the Third Man Tour.)