A simple entrance ticket gets you into the famous treasury of Stift Klosterneuburg. But is it worth the small upgrade fee to do an additional abbey tour?

- Yes, tours are well-worth it for the price

- Access, for example:

- …magnificent imperial rooms

- …medieval cloisters and chapels

- …priceless art (like the Verdun altar)

- …even the wine cellars

- Book a classical concert* in a church or palais

- See also:

Marble and gold

(The Baroque Imperial façade of Klosterneuburg abbey)

Elsewhere, I have general information on visiting Stift Klosterneuburg from Vienna. However, some of the key historical parts remain off-limits to visitors, unless you go on a guided tour. Options at the time of writing include:

- Wine cellar tour plus a wine tasting

- A tour of the abbey (which takes you to the ecclesiastical parts only)

- A grand tour of the abbey (as above, with the addition of the Imperial rooms)

Tours are in German, but you can ask for an audio guide that gives you the same information in English as you go around with the guide.

We took the grand tour, which cost just a few Euros on top of the usual entrance fee and was worth every cent.

After an initial introduction to the history of the abbey and the legend around its foundation, we started with the Imperial rooms built for Emperor Charles VI in the 1730s before he died (and the wider construction project with him).

Marble Hall & imperial wing

(The marble hall within the Imperial rooms; © Stift Klosterneuburg / Alexander Haiden)

First stop was the great marble hall, which seems to be a thing in the Baroque era given both Melk Abbey and Upper Belvedere have a similar room. Marble columns draw your eye up to a ceiling covered with frescoes and illusionist wall paintings.

Remarkably, this hall was only intended as a waiting room for those granted an audience with the Emperor.

No doubt visitors would have been placed there until the weight of all the marble, allegorical paintings and imperial magnificence left them a mortified mess and reluctant to trouble the ruler with demands for tax relief.

(The Speisezimmer within the Imperial rooms; © Stift Klosterneuburg / Alexander Haiden)

We then saw several further imperial rooms, each replete with the usual elegant reliefs, fittings and furniture.

Expect Empire-style upholstered chairs, the kind of writing desk reserved for drafting international treaties, tall rococo candle holders with built-in Japanese vases, damask silk wall coverings, tapestries, and more.

Although just a fraction of the abandoned project for a grand Imperial residence by the Danube, you certainly gain an understanding of what the overall effect would have been like; let’s just say Charles VI was not a man of modest needs.

The abbey church

(The interior of the Stiftskirche; © Stift Klosterneuburg / Jürgen Skarwan)

The Stiftskirche shines almost brilliant white, thanks to recent cleaning and renovation of the façade.

Completed in 1136, much has changed across the intervening centuries. For example, as with so many churches, the interior went through a Baroque redesign. The last big renovation in the 1880s even saw the towers replaced with pointed versions.

Inside hits you with all the magnificence of the Baroque era.

(The Stiftskirche church as it was just prior to the renovation and redesign of the late 19th century; photo by Andreas Groll; Wien Museum Inv.-Nr. 157186/10; excerpt reproduced with permission under the terms of the CC0 licence)

The nave actually becomes progressively less three dimensional in its decoration as you walk down it, reflecting changes in historical trends across the length of time it took to complete the redecoration.

And the 17th-century organ (which Bruckner used to practice on) looks like the kind of astonishing instrument you’d play with a mask covering half your face and a wilting rose on the table next to you.

Cloisters and Verdun altar

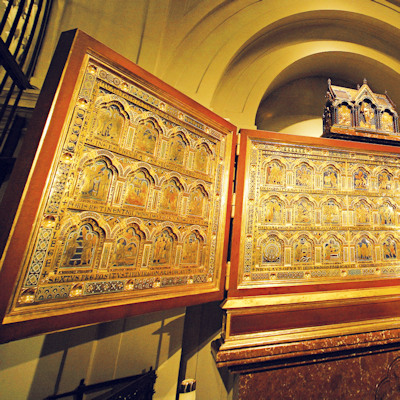

(The Verdun altar; © Stift Klosterneuburg / Jürgen Skarwan)

Then it’s down through the cloisters that date back to the 13th and 14th centuries.

A gold reliquary chest with relics of the abbey’s founder and later saint (Margrave Leopold III) hangs in the Leopold chapel here. Precious though that item is, the true highlight is the Verdun altar below it.

Completed after ten years of work around 1181 in fire-gilt enamel panels, this pulpit panelling was repurposed as an altar piece sometime after 1330.

The long ecclesiastical work depicts stories from the Bible. Rows of illustrations are placed specifically to build connections between the Old and New Testaments.

(The famous artist Egon Schiele painted the abbey cloisters in 1907; Wien Museum Inv.-Nr. 304985; reproduced under the terms of the CC BY 4.0 license; photo by Birgit and Peter Kainz, Wien Museum)

The cloisters and rooms are an authentic dip into medieval history, despite all the rebuilding work of later centuries. You can almost imagine ghosts of the past in wispy cowls and tunics flitting through the edge of your sight.

Here you also discover further gems of the abbey collection, such as:

- The separated back of the Verdun altar: these painted panels done at the time of the repurposing represent a work of art in their own right. They include early (and not entirely successful) attempts at building perspective into the pictures

- A huge bronze candelabra that looks almost tree like. Since the founders gifted this to the abbey, it must date back to before 1136

And just when you think you’ve reached the limits of the journey through time, you pass through a collection of gravestones and remnants of artefacts from Roman times before emerging into the Babenberg courtyard outside.

(Back to the Klosterneuburg abbey overview.)