Art and politics make uneasy companions. Especially when those politics are totalitarian. The Vienna Falls in Line exhibition explores the dynamics of the relationship between fascist authorities, art and artists during Nazi rule in the city.

- Looks at individuals, artwork, and institutions in an era of art controlled by political influence

- Quite an eye-opener (a remarkable job by the researchers and curators)

- Hosted at the Wien Museum MUSA

- Runs Oct 14, 2021 – Apr 24, 2022

- See also:

- Current MUSA visitor and exhibition info

- Current history and other exhibitions in Vienna

Vienna Falls in Line

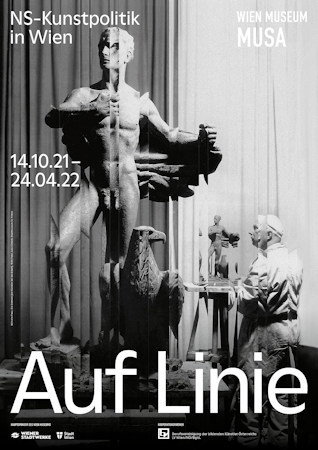

(Exhibition poster, Vienna Falls In Line. The Politics Of Art Under National Socialism, Wilhelm Frass The Ostmark (The Artist at Work), 1939; photo by Julius Scherb | Municipal Museum St. Pölten; graphics by seite zwei)

The catastrophic period of fascism in the 1930s and 1940s remains a stain on Austrian history. And it still has ramifications for today.

Consider, for example, the issue of artworks produced at the time. You can imagine the kind of questions museums must (still) ask.

For example, where do you draw the line between art and propaganda? How do the political leanings of an artist impact their legacy and the evaluation of their work? And what’s to be done with that work?

Such questions match the Zeitgeist, as we confront the issues around, for example, statues that celebrate those of dark morals.

The Vienna Falls in Line exhibition takes a look at that fascist era, drawing on a remarkable research project that examined the membership of the Reichskammer der Bildenden Künste (Reich Chamber of Fine Arts).

Joining the Reichskammer was a requirement for anyone wishing to make a vocation of their creativity and enjoy public patronage.

As you might imagine, membership remained closed to those without approved racial, political and artistic credentials. Painters, sculptors, etc. of Jewish heritage, dissidents and the inappropriately avant-garde faced an effective employment ban policed by the Gestapo.

(One exhibition item, for example, is an application form which asks how many of the applicant’s grandparents are Aryan.)

Vienna Falls in Line uses original art, objects and documents to illuminate the impacts of such control and coordinated political direction on those who “fell into line” (or did not) and also traces the fates of various artists during and after the period of national socialism.

Various displays explore the production of art for propaganda purposes, highlight the role of the Viennese authorities as patron of “approved” art, and scrutinise the special cases of those artists who enjoyed particular privileges under Nazi hegemony.

The result is a critical exposition of an era that presents museums, curators, and art lovers with numerous challenges given the horrendous nature of the period.

(The exhibition is a cooperation with the Vienna, Lower Austria and Burgenland section of the Berufsvereinigung der bildenden Künstler Österreichs: the national professional association of practitioners of the fine arts, and an organisation itself forced to endure a period of insignificance during the Nazi years.)

Personal impressions

(Exhibition posters outside the venue)

The researchers and curators have put together quite an eye-opener, especially for those unfamiliar with the nazification and denazification of Vienna and Austria.

We get insights into the darker side and opportunism of the human spirit. So, for example, we discover how some artists and artist groups were already positioning themselves for favour even before the Germans marched into Vienna.

We explore the complex bureaucracy behind an extremist ideology. The longwinded process involved in approving artists to ensure conformity to the Nazi ideals could reach as far as Goebbels himself.

We are implicitly invited to consider the difficulties of evaluating the artist members of the Reichskammer. How many “approved” artists were believers and how many were simply playing the system? How should they and their work be judged?

We learn about the harsh inequities of life, since not every complicit or Nazi artist paid a price for that complicity or their views in post-war Austria. Many got a metaphorical slap of the wrist and later reinstatement as a member of the artist community.

(Nor were all those excluded properly compensated: many were persecuted and murdered by the Nazi regime or forced to emigrate never to return.)

We gain glimpses of an alternative cityscape scarred by Nazi ideology in the form of proposed designs for reconstructed city areas, such as decorative Nazi pillars outside the state opera house. A startling painting of Heldenplatz by Robin Christian Andersen has the square decked out in Nazi flags.

The exhibition packs a great deal into a small space and is a fitting tribute to the research work behind it: a long overdue examination of the topic.

Dates, tickets & tips

Learn about Nazi influence on art and artists from October 14th, 2021 to April 24th, 2022.

A ticket for the Wien Museum MUSA cost €7 for an adult (kids went free), but the location has since moved to free entry for all (at least at the time of writing).

Wall text and exhibit labels are all in German and English. Obviously, being able to read some of the original documents in German would add to your experience.

How to get to the MUSA

Follow the directions given for the Wien Museum MUSA. The Vienna Falls in Line exhibition fills the main gallery on the left as you go in and buy your tickets. Start at the back (exhibition areas are numbered to guide you through the experience).

Should you wish to learn more about the impact of the Nazis on Vienna, then the House of Austrian History in a wing of the central Hofburg complex has a section covering those years.

Another useful (and poignant) address is the Jewish Museum.

Address: Felderstraße 6-8, 1010 Vienna