Many art exhibitions in Vienna focus on “prints”. But what do all the technical terms in display texts and audioguides actually mean?

I’m no art historian or expert (so feel free to click away or suggest corrections), but here’s my simple explanation of common printmaking words used in these exhibitions.

Consider it a glossary that covers the basics, so you can tell your lithographs from your etchings.

- See also:

- The Albertina Museum (they own a huge and prestigious collection of prints, some of which are often on display in special exhibitions)

- Art exhibitions in Vienna

Jump to:

- What is a print?

- Woodcut

- Engraving

- Etching

- Lithograph

- Screenprint

- Other terms

- Linocut, Chiaroscuro, Intaglio, Mezzotint

- Where to see prints

What is a print?

It seems my poster of AC/DC’s 1985 Fly on the Wall album cover does not count as a print in the truly artistic sense.

Damn.

So what, then, is a print?

These seem to be the key characteristics in the context of most art exhibitions:

- The artist has an image in mind as an original piece of art to be produced on (mostly) paper

- They do not create the image directly on the paper (as with a pen drawing or watercolour painting, for example)

- Instead, they create a design on the surface of some hard material, which we might call a printing block or plate or matrix (but also see the screen print below)

- When covered in ink and pressed down on paper, this block leaves behind the image conceived by the artist. (The final image may require several printing iterations to introduce tones, colours, etc.)

- What you get at the end of that process is a “print.”

Most of art history needed that hard material as a means of creating prints. Today, artists obviously have access to more printing choices than the above, including digital alternatives.

Incidentally, the creation of the printing block and/or the actual printing process may involve collaboration with a skilled craftsperson and use of specialist printing materials and equipment.

The repeatability of the printing process has always allowed an artist to produce (i.e. print) multiple copies of a work for sale or distribution. However, art prints tend to be few in number, i.e. produced as limited editions.

The low number of available prints of a particular image (which may also be due to the ravages of time in the case of historical art) and the direct involvement of the artist is why prints have artistic and monetary value.

Those terms you find bandied around in exhibitions arise largely from differences in the base material used for making the printing block and how the printable image is created in that base material.

The printing method and base material (and the paper!) also change what’s possible in terms of the resultant printed image, a fact that artists exploit in creating unique works.

Common printmaking techniques

We begin with…

The Woodcut

(Christ Expelling the Money Lenders, from “The Small Passion” by Albrecht Dürer around 1508. Image courtesy of the Met Museum.)

The print first appeared centuries ago in the form of the woodcut.

The artist takes a flat piece of wood and cuts or chisels away parts of the surface with a tool to leave protruding areas that make up a desired image in relief. Like kids do with a cut potato to make simple prints in Kindergarten.

Ink is applied (for example using a roller) only to those protruding areas and then the woodblock is pressed down on paper to create the desired image.

The bits cut away receive no ink or can’t touch the paper and so leave a blank space between the inked areas. Here’s a detailed explainer with animations from the Met Museum.

Obviously, the outcome depends on the skill of the artist / craftsperson and the ability of wood to support delicate protrusions or narrow gaps for fine lines and detail.

Engraving

(Hercules and Telephos, engraving by Hendrick Goltzius, 1617. Image courtesy of the Rijksmuseum)

For an engraving, the artist takes a flat piece of metal and uses a sharp tool (a burin) to scratch out very shallow lines and hollow areas in the metal surface.

Ink is applied across the entire surface and then wiped off. Contrary to a wood cut, then, ink typically only remains in the scratched lines and hollows.

When paper is pressed down tightly on the metal surface, the ink is again transferred to the paper to create the image.

The main advantage over the woodcut is the level of detail and subtlety possible.

Here’s the Tate’s explanation.

Etching

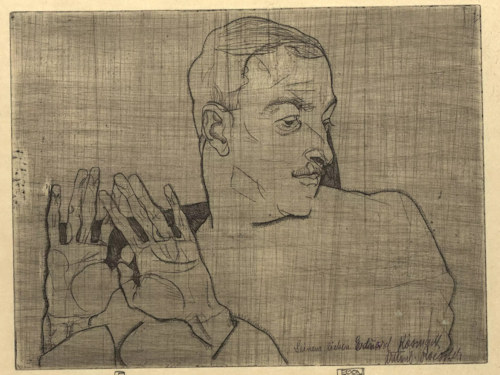

(Arthur Roessler, 1914, portrayed by Egon Schiele; Wien Museum Inv.-Nr. 94262; excerpt reproduced with permission under the terms of the CC0 licence)

An etching uses a similar concept to engraving. However, the lines and depressions in the metal surface arise through a different technique.

The artist first covers that metal surface with an acid-resistant material like a wax. They then scratch out the design in that top layer exposing the metal below.

In the next step, the artist applies acid across the metal plate. Only exposed metal lines and areas get eaten into by the acid. Artists can vary how long they allow the acid to work at the metal.

Once done, the acid-resistant material is cleaned off and you have a design left etched into the metal surface. Add ink and print as above.

A main advantage over engraving is speed; it’s much easier to scratch out a design in soft wax than hard metal.

Here’s a more detailed explanatory video from the National Museums Liverpool.

The Lithograph

(August Prinzhofer by the painter Johann Peter Krafft (1780–1856), 1847, Lithograph, 55 x 35,5 cm, Belvedere, Wien, Inv.-Nr. 7626; photo courtesy of and © Belvedere, Wien. Reproduced with permission under the terms of Creative Commons License CC BY-SA 4.0.)

The lithograph is a little more complex than what we’ve seen so far.

Essentially, the artist draws an image directly onto a flat stone surface using a special ink or crayon. Various kinds of chemicals are then applied that:

- Bind the applied ink/crayon to the stone’s surface

- Prepare that surface to take ink for printing

- Ensure the drawn elements take up this printing ink

- Ensure the parts the artist wishes to remain blank don’t take up ink

Then an adapted version of inking and pressing suited to the stone printing block takes place.

An advantage over previous techniques is, for example, smoother images.

Here’s the Met’s animated explanation.

Screenprinting

And another complex printing process that I won’t go into in detail (largely because I don’t know the detail).

All the above involve pressing paper down on an inked surface in one way or another to leave an imprint.

In a screenprint, ink is applied across a permeable screen that covers the paper. Ink squeezes through the screen to leave a print on the paper.

An image arises by ensuring parts of that screen do not let ink through. Think of that screen as a selective filter that works a bit like a stencil.

In the past, tightly-stretched silk largely served as the screen (you see a lot of silk screenprints by Andy Warhol, for example), but various materials serve the same function.

Of course, the clever bit is creating the mix of permeable and impermeable areas on the screen for which various physical and chemical methods can be used.

Here’s the Tate’s explanation.

Other terms

The Linocut

Like the woodcut, but uses linoleum instead. The material is easier to manipulate but not so great at holding its structure and allowing finer detail.

Chiaroscuro

A general art term for the stylised use of light and dark areas im images. Also used specifically in woodcuts to refer to printing successive woodcut designs on a piece of paper to create different tones on the final outcome.

Intaglio

A term used to describe those forms of printmaking where the ink is applied to the parts cut away (as in engravings or etchings). As opposed to a woodcut, where the ink goes on the parts not cut away (relief printing).

Mezzotint

A technique where a special tool is applied to roughen areas of a metal surface so little dimples appear that take on ink.

The intensity of the roughening (or subsequent polishing) allows finer shades in, for example, etchings or engravings that would otherwise only rely on lines and crosshatching to create areas of light and darkness.

And there you have it.

Where to see prints

In Vienna, many special art exhibitions likely include prints among the works on display.

A current example (until September 1st, 2024) is the Viennese Nostalgia exhibition featuring the etchings of Emil Singer from the early 1900s.

However, do check the Albertina or Albertina Modern, in particular. The Albertina institution has over a million items in its drawing and prints collection; these often find their way into exhibitions.

2023’s Great Masters of Printmaking, for example, featured such names as Dürer, Bruegel, Rembrandt, Goya, Canaletto, Manet, Toulouse-Latrec, Munch, Chagall, Matisse, and Hockney. (My visit there actually prompted me to write this post.)